Another Split-Flap Display Board

Table of Contents

Background

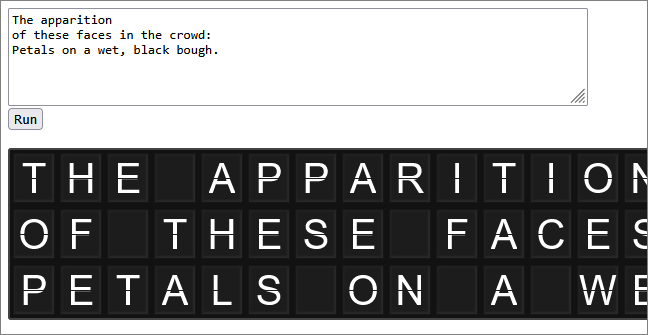

First, here is a runnable demo of the code.

And here is the source in GitHub.

And if you want to know more about split-flap displays, read this.

I used to love those old giant message boards in train stations. It’s not the same with digital displays, without the sights (and sounds) of the letters all rotating at once.

Inspired By…

I was inspired by these great examples:

- https://gist.github.com/veltman/f2b2a06d4ffa62f4d39d5ebac5ceeef0

- https://github.com/paulcuth/departure-board

And you can also get really fancy - such as with this one which really pulls out all the stops, but also uses far more visual features (and libraries) than I wanted to attempt.

A Note on the Code

None of this makes any concessions to older browsers, which may not support some of these more recent features. I did this exercise purely for myself. I wanted to use an array of JavaScript Promises, and avoid any third party libraries - just core JavaScript.

Splitting Letters

Each letter in the message is actually displayed in two divs - one which shows only the top half of the letter and one which shows only the bottom half of the same letter. Because they are independent divs, I can use this to display the top half of the letter slightly before I display the bottom half - thus simulating the physical flip of the letter on the board.

(Another way to go would be to use CSS transitions - but I don’t use any of those here.)

I split each letter (or symbol or glyph) into two independent halves (top half and bottom half) and then place the bottom element so it exactly covers the top element (see position: absolute below).

I hide half of each letter using the following CSS (see here):

|

|

The key parts are background: linear-gradient, which forces the top half of the div to be white and the bottom half to be transparent (and vice versa for the second div).

This is then combined with background-clip: text, which causes the linear gradient to be applied only to the shape occupied by the letter - very cool!

The Display Grid

The user-provided message is displayed in a rectangular grid - so the code re-arranges the message to pad each line to the length of the longest line. This is all handled by the set-up section of the JavaScript.

Not much to say about this.

Controlling Each Display Cell

I control each display cell independently by launching an array of asynchronous displayCell() functions. There is one function per cell in the message grid.

The array of functions is loaded here. I also load an array of parameters. Each of these parameters is an object containing the info each function needs to control its cell. For example, the function needs to know what letter should be displayed in its cell. The function also needs a list of displayable characters which the function will iterate through, one-by-one until it finds the letter which needs to be displayed.

Launching an Array of Async Functions

To fire off all of these processCell() functions, I use the following code:

|

|

The map() method ensures each function is handed the specific parameters it needs - and the function is then dynamically invoked by func(paramsArray[index]). But because the processCell() function is asynchronous, the cellTasks variable is given an array of Promise objects (one for each cell in the display).

Tracking Each Cell’s Progress

I want to know when all of the async functions have completed (when the promises are fulfilled). Here is that code:

|

|

The above code can be boiled down to the following simplified syntax:

|

|

The first time I saw this type of JavaScript I had no idea what I was looking at.

It’s an immediately invoked function expression (IIFE). It is a self-executing anonymous function. That is indeed quite powerful!

In our case it’s also asynchronous (using async-await).

The following line in our IIFE…

|

|

…is how all of our asynchronous functions are tracked and how all their outcomes are reported back to us at the end (in results). The use of Promise.all() is a convenient way to get all of the results we need.

This is a reminder (to me) that using async and await is just another way of working with Promise objects - and that the two idioms can be combined where it makes sense to do so.